Source: Public Library

Paperback, 85 pgs

I am an Amazon Affiliate

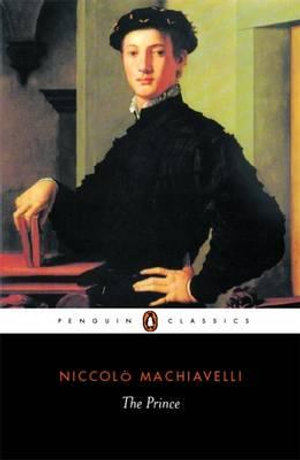

The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli, which was our June book club selection and my second reading (I haven’t read this since college), is a nonfiction analysis of different types of principalities and how a prince can keep them when factions or people move against him. The work is considered a classic and it is an examination of what traits make principalities hard to maintain or easy to keep, as well as what characteristics a prince should foster in himself to hold onto his principality. Although this is a slim volume, the economy of the language makes it quite dense and oftentimes dry. Many often attribute the sayings of “the ends justify the means” and “might makes right” to Machiavelli, though they are not necessarily accurate interpretations of what he espoused.

It is clear that his life experiences as a civil servant in Italy, which had been far from unified under one government and was operated more through a balance of various factions and the strength of the truth. It is clear that Machiavelli viewed political success from a practical standpoint, without an emphasis on morality. More accurate attributions of wisdom to him might be that you can gauge the intelligence of a prince by those he has around them or that it is better to be feared than loved.

“The main foundations of every state, new states as well as ancient or composite one, are good laws and good arms; and because you cannot have good laws without good arms, and where there are good arms, good laws inevitably follow … ” (page 40)

The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli has become a guidebook for many leaders, and has been perverted by others, including Hitler and Stalin. Whatever readers may take away from his advice on principalities, Machiavelli is clearly a keen observer of human behavior, especially among rulers. It is highly humorous that he would give this book as a gift to a new ruler of the Medici family in the hope of gaining favor with the new government, especially since the book tends to provide a framework for governing as if the reader would need pointers. How many rulers would take to that kindly?

What the book club thought:

Everyone seemed to agree that this was almost like a how-to guide on how to become a prince and maintain the power they gain, regardless of the political or geographical situation. One member expressed the opinion that Machiavelli seemed to focus on his own ambitions, despite his couching of his advice as something to help Medici, who was currently in power at the time the book was written. Others did not see that, and I mentioned that he was incredibly disappointed that his political and civilian government life had come to an end too quickly and that he was motivated to ensure his return to that life. Overall, most people found the book interesting and though that it would be interesting to see what Machiavelli would have written about the U.S. presidency or if his guide would work in today’s modern world. The book generated a great deal of discussion, and most were surprised that it was not more evil than they expected.

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author: