From "Prodigy": It is youth that keeps you pale and concerned about the smaller buzzing parts, the soil and the pine cones there, and the grace between fists and teacups. You are a foil, a reminiscence, a sobering glance forward because nothing can be repeated, metric by metric; speaking the dream always changes it irreparably, as if it weren't worth mentioning.

From "Apollo at 21st and 8th": record we shed each day, the accumulation of our pasts that we deposit upon wood and polish, in the shafts and patterns of directed sunlight. Could gods begin in dust and spit not as we have,

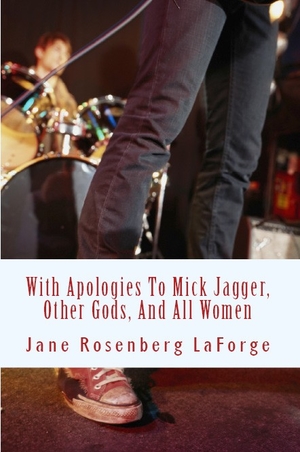

The collection is divided into two parts, and the first section, despite the title of the Mick Jagger poem, are hardly apologetic. From the crass way that age takes over the face to the abandonment of religion and faith in favor of the present and those rock stars before us on the television, LaForge chooses terse language clipped in the right places to give readers enough pause to encourage serious contemplation about aging and worship of the present. In “Runyon Canyon,” her narrator says, “It is not the soul that grows/in your bone, but a whistle;/as if a palpable friction between/lip and reed; a green-sweet taste/like hesitation and sympathy;” These images blend together to create a sound that hums.

In the second half of the collection, the poems are more personal, delving into the sorrowful images of disease and how the body can be ravaged even when the patient is in denial or at least trying to pretend they are not ill. LaForge takes a frank look at the grotesque found in the most beautiful relationships, including being sisters. With Apologies to Mick Jagger, Other Gods, and All Women by Jane Rosenberg LaForge strikes a pose and has an opinion without apology, and don’t expect one. The statements are bold and without explanation. They just are.

Jane Rosenberg LaForge’s poetry, fiction, critical and personal essays have appeared in numerous publications, including Poetry Quarterly, Wilderness House Literary Review, Ottawa Arts Review, Boston Literary Magazine, THRUSH, Ne’er-Do-Well Literary Magazine, and The Western Journal of Black Studies.

This is the 23rd book for my 2012 Fearless Poetry Exploration Reading Challenge.

The title of the collection tells readers all they need to know about the topics covered, including the moral, mental, and physical slavery or servitude as well as the complete emotional absorption that can happen in relationships. As Trethewey examines works of art through a lens of racial demarcation, she also looks at daughters’ relationships with their fathers, which can sometimes be congenial and at other times turbulent. In “Knowledge,” she is looking at the dissection of a woman and the men who stand around her as the cut is made into her flesh, and Trethewey’s narrator concludes that her father was not just one type of man, but each of the men in the room — all at once contemplative, scientific, and artistic, even though at times she felt he were just one of those men.

The title of the collection tells readers all they need to know about the topics covered, including the moral, mental, and physical slavery or servitude as well as the complete emotional absorption that can happen in relationships. As Trethewey examines works of art through a lens of racial demarcation, she also looks at daughters’ relationships with their fathers, which can sometimes be congenial and at other times turbulent. In “Knowledge,” she is looking at the dissection of a woman and the men who stand around her as the cut is made into her flesh, and Trethewey’s narrator concludes that her father was not just one type of man, but each of the men in the room — all at once contemplative, scientific, and artistic, even though at times she felt he were just one of those men.

Out of True by Amy Durant, blogger at

Out of True by Amy Durant, blogger at

The Wonder of It All

The Wonder of It All