Paperback, 479 pgs.

I am an Amazon Affiliate

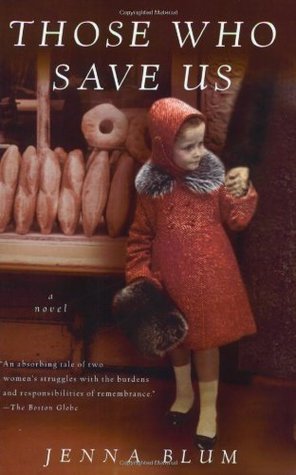

Those Who Save Us by Jenna Blum, which was the readalong selection for June at War Through the Generations, is a complex story in which Anna Schlemmer has kept her activities during WWII in Weimar secret, even from her daughter Trudy. Although Trudy was a young girl during the war, she remembers very little and what she does remember often comes to her in snatches of dreams and makes little sense. She’s tried to pry the past out of her mother ever since finding a portrait of herself, her mother, and a Nazi SS officer in her drawer at their farm in New Heidelberg, Minnesota.

“It is one of the great ironies of her mother’s life, thinks Trudy Swenson, that of all the places to which Anna could have emigrated, she has ended up in a town not unlike the one she left behind.” (pg. 73)

Blum’s novel shifts from the points of view of Anna and Trudy and shifts in time from WWII to the 1990s, where Trudy has begun a project to interview Germans about their time during the war, as her colleague strives to save the stories of Jews who escaped the Holocaust. But this story begins with a young girl looking to get out from under her father’s thumb in Germany, as war is beginning to seem more likely. Anna falls for a young man, and their relationship is doomed from the beginning. What transpires from that love affair onward takes Anna on a journey into darkness where she is alone and very aloof, even from the local baker, Mathilde Staudt, who agrees to take her in.

“It is as though Trudy has reached under a rock and touched something covered with slime. And now she is coated with it, always has been; it can’t be washed off; it comes from somewhere within.” (pg. 185)

Anna’s silence looms large over Trudy’s life, and it has foisted guilt upon her for a time she barely remembers and a man she suspects is her father. Her guilt is compounded by her mother’s unwillingness to talk about the past and the death of her stepfather, Jack – a former WWII soldier for America. Along the way, Trudy meets an older man who is half Jewish, Rainer, and she begins to see that her happiness does not have to be tied to the past.

Those Who Save Us by Jenna Blum explores generational guilt and the effects of war atrocities on those who did not commit them but were considered just as guilty as those with whom they associated. Blum’s research is impeccable and her understanding of the guilt and horror of the Holocaust and WWII emerges in the characterization of Anna, Trudy, and so many other secondary characters. Readers will be submerged alongside Anna as she struggles to survive for herself and her child, doing things she would prefer not to. She is forced to remain practical and to deal with any one she encounters with suspicion and caution, and when the past is on another continent she wants her daughter to leave it there. Although I would have preferred greater resolution between Anna and Trudy — whose relationship appears broken from the start of the novel — the ending does provide some hope. The novel carefully explores the question of whether we can love those who save us even as they commit the most heinous crimes and whether the past is best left where it is in order for happiness to be found.

RATING: Quatrain

Read the discussions:

About the Author:

New York Times and internationally bestselling author of novels THOSE WHO SAVE US (Harcourt, 2004) and THE STORMCHASERS (Dutton, May 2010) and the novella “The Lucky One” in GRAND CENTRAL (Berkeley/Penguin, July 2014). One of Oprah’s Top 30 Women Writers. Novel THE LOST FAMILY forthcoming from Harper Collins in Spring 2018.

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

The title of the collection tells readers all they need to know about the topics covered, including the moral, mental, and physical slavery or servitude as well as the complete emotional absorption that can happen in relationships. As Trethewey examines works of art through a lens of racial demarcation, she also looks at daughters’ relationships with their fathers, which can sometimes be congenial and at other times turbulent. In “Knowledge,” she is looking at the dissection of a woman and the men who stand around her as the cut is made into her flesh, and Trethewey’s narrator concludes that her father was not just one type of man, but each of the men in the room — all at once contemplative, scientific, and artistic, even though at times she felt he were just one of those men.

The title of the collection tells readers all they need to know about the topics covered, including the moral, mental, and physical slavery or servitude as well as the complete emotional absorption that can happen in relationships. As Trethewey examines works of art through a lens of racial demarcation, she also looks at daughters’ relationships with their fathers, which can sometimes be congenial and at other times turbulent. In “Knowledge,” she is looking at the dissection of a woman and the men who stand around her as the cut is made into her flesh, and Trethewey’s narrator concludes that her father was not just one type of man, but each of the men in the room — all at once contemplative, scientific, and artistic, even though at times she felt he were just one of those men.

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author: