From "All You Need is Touch" (Page 75): Feeling like a pain in the ass Is no fun for anyone But I get by every day By needing Basic life functions

From "Big Mouth" (Page 50): Do not treat me with distrust For I have not lied Only told the truth too much

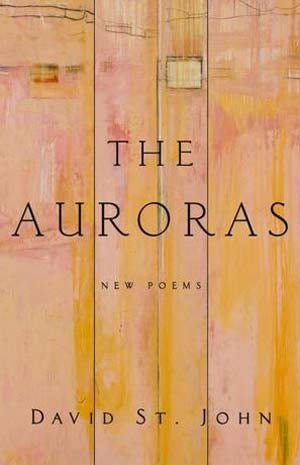

Some poems are more typically poetic than others, but it is clear that writing is an outlet for Naught as he struggles daily with his lack of physical freedom and desire for more out of life. From “Lack of Physicality” to “Movie in Mind,” Naught’s poetic talents shine as he weaves in images to display how we are all human and struggle with our own limitations. These are the gems of the collection. Readers may want to dip into the collection over a period of time rather than read it from beginning to end so that they can take in the heavy emotions put forth by the narrator. The Virgin Journals by Travis Laurence Naught is a good debut from a writer who clearly has more to say and more to explore in terms of poetry and prose.

Poet Travis Laurence Naught

About the Poet:

Travis Laurence Naught is poetry/prose writer … college graduate … former Division 1 college men’s basketball assistant … quadriplegic wheelchair user. Join him on Facebook and on Twitter.

***For today’s National Poetry Month blog tour stop, go to the bookworm.***

This is the 5th book for my 2012 Fearless Poetry Exploration Reading Challenge.

About the Poet:

About the Poet:

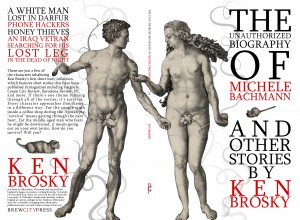

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author: