Synopsis –

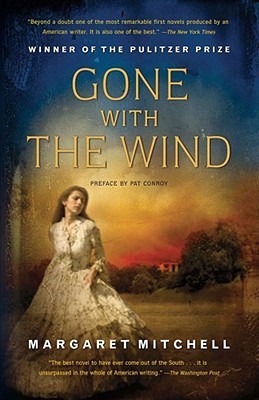

Since its original publication in 1936, Gone With the Wind—winner of the Pulitzer Prize and one of the bestselling novels of all time—has been heralded by readers everywhere as The Great American Novel.

Widely considered The Great American Novel, and often remembered for its epic film version, Gone With the Wind explores the depth of human passions with an intensity as bold as its setting in the red hills of Georgia. A superb piece of storytelling, it vividly depicts the drama of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

This is the tale of Scarlett O’Hara, the spoiled, manipulative daughter of a wealthy plantation owner, who arrives at young womanhood just in time to see the Civil War forever change her way of life. A sweeping story of tangled passion and courage, in the pages of Gone With the Wind, Margaret Mitchell brings to life the unforgettable characters that have captured readers for over seventy years.

Today’s review is from Elisha at Rainy Day Reviews.

Gone With the Wind is a classic for a reason. Well written, timeless, and tells a story of bravery, heart, and the difficulty of living life during the Civil War. I can see why people would call this novel a romance however, I would not call this a romantic read but a dramatic read with romance as a key part of the novel. Even though I was not a big fan of Scarlett, she had backbone and had to learn rather quickly that life was not always as easy or pleasant as she once thought due to the civil war and the surrounding issues of life then on the plantation. All around a great book and I can see why the movie is four hours long and look forward to watching it (I still haven’t seen it).

I most definitely would recommend this read for all.

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

In the surreal and paranoid underworld of wartime Prague, fugitive lovers Felix Andel and Magdalena Ruza make some dubious alliances – with a mysterious Roman Catholic cardinal, a reckless sculptor intent on making a big political statement, and a gypsy with a risky sex life. As one by one their chances for fleeing the country collapse, the two join a plot to assassinate Hitler’s nefarious Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Josef Goebbels. But the assassination attempt goes wildly wrong, propelling the lovers in separate directions.

In the surreal and paranoid underworld of wartime Prague, fugitive lovers Felix Andel and Magdalena Ruza make some dubious alliances – with a mysterious Roman Catholic cardinal, a reckless sculptor intent on making a big political statement, and a gypsy with a risky sex life. As one by one their chances for fleeing the country collapse, the two join a plot to assassinate Hitler’s nefarious Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Josef Goebbels. But the assassination attempt goes wildly wrong, propelling the lovers in separate directions.