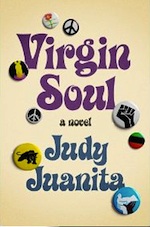

Source: Viking

Hardcover, 306 pages

I am an Amazon Affiliate

The rhythm of Virgin Soul by Judy Juanita’s narrative is reminiscent of scat singing, but with a street-based undertone, jumping from moment to moment creating an atmosphere that resembles the turbulent nature of the 1960s. In this way, she captures the atmosphere, especially among African-Americans in California at that time, really well. The protagonist Geniece Hightower has always felt like an outsider since her mother died and her father skipped out, but when she heads off to college, she thinks that she’s finally found a place to fit in. She meets some people engaged in the civil rights movement, and falls in love with Allwood, who becomes her lover and teacher. She falls in and out of relationships, but at her heart Allwood is her first love.

Juanita breaks the book into one year of college from Freshman to Senior year, and its first-person narrative makes it read more like a memoir than fiction. The novel bounces from moment to moment, reading more like a journal than fiction, and Geniece is tough to get a handle on as she’s pulled between the moral and conservative views of her family and the angrier, more liberal thinking of her friends.

“Uncle Boy-Boy was a dentist and Aunt Ola Ray was his wife and I was not their adored child–I was more obligation than kin, their dark-skinned orphan-in-residence. I had gotten accepted into SF State as a freshman, but my ‘financial resources’ amounted to my seventy-two-dollar monthly Social Security check. I wasn’t about to ask them to support me.” (page 3)

Geniece is looking for her place in the world, and as she’s felt like an outsider in her own family, it’s easier for her to be captured by the passions of others, and eventually, she falls into the Black Panthers. While she’s caught up in the movement, she never loses sight of getting her education, knowing from her family that it is about the only way she can break free from poverty. As a member of the party, she learns that she is as angry as the men in the party, but she draws the line at killing. Geniece never seems to grow out of the naive way in which she relates to the men in her life — falling into bed at a moment’s notice, even when there is very little attraction — but her relationships with her female friends are at arms length in most cases.

“Whenever Allwood insisted, I resisted, but only to a point. I wanted to know what he knew, feel what he felt inside that righteousness. The only way in was to surrender, and I was willing. I had plenty of motivation and a demonstrated interest, but I needed a catalyst. Allwood was the reason I became black.” (page 35)

Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the leaders of the Black Panthers, are here, along with many others from history, but they are more in the backdrop than in the foreground. Other figures from history include Stokely Carmichael, Betty Shabazz, Eldridge Cleaver, and more. Geniece, however, is on the sidelines and working with the community and the children and on the paper, but she has little to do with the violent protests and demonstrations. She’s a bystander, but she isn’t. Her involvement is focused on the rebuilding of the community, and in this way, her character matures and becomes a focal point for what was good about the Panthers. Readers looking for an in-depth connection to these historical figures will be disappointed because the novel’s focus is Geniece and her experiences during the 1960s and the civil rights movement, which also gets caught up in the controversy of the Vietnam War and the deaths of Black soldiers on the front lines.

When the police and the FBI are watching your every move, it is naive to think that even as a mere writer or community volunteer that you wouldn’t be a target. Unfortunately, Geniece is very naive in terms of precarious situation as a party member — a perception that she has to face head on later in the book. Moreover, it seems as those she simply falls into a socialist movement, and gets herself deeper involved without thinking about the consequences. Where the novel failed is at the end where too many things are left unresolved and hanging, and Geniece’s character is only partially evolved beyond her first introduction. The relationships between the main character and the male party members are vague at times or seemingly non-existent until they fall into bed.

Virgin Soul by Judy Juanita is not for every reader; it is definitely frank about the 1960s movements, the violence, the drug use, the rampant sexual activity without commitment, and the paranoia that many in the African-American community felt. However, Juanita has a firm grasp of her setting and time period, making it easy for readers to transport themselves back in time and to feel the tension and paranoia that these activists felt as they strived for change. Another aspect that comes to life is the color differences and prejudice within the Black community itself, particularly in how darker skin men and women were treated compared to those with lighter brown skin. Overall, a turbulent novel that reads more like a series of memories.

Judy Juanita’s poetry and fiction have been published widely, and her plays have been produced in the Bay Area and New York City. She has taught writing at Laney College in Oakland since 1993. This is her first novel. She lives in Oakland. Check out this Interview from Publisher’s Weekly.