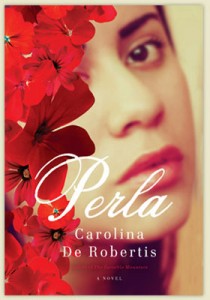

Today, I’ve got an interview with Carolina De Robertis about her book and The Disappeared. Without further ado, please give her a warm welcome.

Writing about the disappeared of Argentina must be quite a balancing act even after many decades. What inspired you to take on the subject and why choose to tell the story in a way that is at times surreal and very focused through the eyes of Perla?

My interest in the subject first arose from the extensive research I did for my first novel, The Invisible Mountain, which traverses ninety years of Uruguayan history, among them the revolutionary 60s and the dictatorship of the 70s and 80s. Inevitably, in studying those times, I also encountered the realities that unfolded on the other side of the river, in Argentina. It was more than could possibly fit in one novel, and inspired me to “cross the river” for my second novel, to Argentina, where I also have roots and relatives.

The surreal premise of Perla originally came as a vivid image I couldn’t get out of my head, of the disappeared who were thrown into in the river from airplanes, rising back up to visit the living. It wasn’t an intellectual decision. However, looking back, I think I was drawn to this choice because it allowed me to do something I haven’t seen anywhere else in the literature and filmography of the disappeared, which is to give the disappeared a voice of their own, to explore their side of the story in an immediate way. And telling the story through Perla, a military man’s daughter, allowed me to do something else that I hadn’t seen elsewhere, and that seemed urgent to me: to attempt to portray the full humanity of perpetrators of these crimes, without excusing them. Who would more honestly grapple with that difficult humanity than a perpetrator’s beloved daughter?

How much has the political landscape changed between when the disappeared were taken and today? Did that play a role in how you tackled the subject in fiction and were there any lingering concerns about how you portrayed the past in your fiction?

When the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo first started organizing, in the late 70s, to defend the rights of their disappeared adult children, they were putting their lives at risk (and some of them in fact lost their lives as a result). Today, the Mothers have been honored in the Presidential Palace and are widely celebrated as heroines. Argentinean public opinion has come to decry the human rights abuses of the regime. Nevertheless, the wounds of those times are still viscerally alive in Argentinean society, in many ways. So I knew that I’d be touching on a national wound. I could only hope that the potential of art to create beauty and healing out of horror would outstrip the pain of having brought it to the surface.

The character of Perla is very complex in that she has a certain identity that is challenged from an early age given who her father was in the 70s and 80s. Did you have an outline of her character before you began writing her? Were there things about her character that surprised you? How so?

There were many things I knew about Perla when I began to write her into being, including the various layers of secrets that lie in her and in her family. However, I learned a great deal more about her as I wrote. In some ways, she is more vulnerable than I initially thought her to be. In other ways, she’s a great deal stronger than I first painted her. She has a wild streak. She also has a sense of humor that I didn’t see coming, which really emerges in her love affair with Gabriel, and which gives her another level of resilience.

Are there particular books you’d recommend to readers who want to learn more about the disappeared? Which ones and what makes them a must read?

There are many important books, but one of the most eloquent and devastating is Prisoner Without a Name and Cell Without a Number by Jacobo Timerman. Timerman was a respected journalist who was “disappeared” under the dictatorship, and only survived because international pressure forced his release. On his release he wrote this slim, amazing memoir that propels you right into the experience. I’d also recommend the Oscar-winning film The Official Story, which unfolds the world of a mother who begins to suspect her adopted daughter may be a child of the disappeared.

In the acknowledgements, you mention receiving Nunca Más. Upon reading the book, how has your world view changed and do you see your fiction writing as way to reveal to the world the deeper questions that events like the disappearance of Argentinians raise?

A book like Nunca Más, which gathers the testimonies of survivors of atrocity, is bound to shake you and your sense of the world. It forces you to look in the eye some of the tremendous cruelties we human beings are collectively capable of. How can such things happen? And why do they keep happening in so many places across the world? Most importantly, how does a society begin to truly move beyond such a tragedy and affirm the beauty and powerful forms of love that are also part of human experience? I do think that fiction plays a particular role in exploring such questions. Fiction can delve into the long-term, intimate effects of violence, and the complex and often astounding ways that people rebuild their lives. Fiction can open doors to healing, to awakening, and to fresh explorations of the truth. This may sound a bit hyperbolic, but I really do believe this, perhaps because, as a reader, novels have done all these things for me.

Finally, who are some of your favorite authors and poets? Or what are you reading now that you enjoy?

There are so many! Just a few of the authors I constantly turn and return to: Toni Morrison, Virginia Woolf, Gabriel García Márquez, Italo Calvino, Clarice Lispector, Walt Whitman, William Faulkner, Herman Melville, Dostoevsky. As for recent reading, I just finished The Danish Girl by David Ebershoff. It’s a portrait of Einar Wegener, the first person to successfully undergo male-to-female sex change surgery—and a stunning novel, told in the most vibrant, nuanced, and utterly unforgettable voice.

Thanks, Carolina, for answering my questions.