Peter Schilling Jr.‘s The End of Baseball is his debut novel, new in paperback this month. Set in 1944 during World War II and at a time when African-American baseball players were being integrated into the major leagues, the novel follows young Bill Veeck Jr.‘s foray into baseball team ownership and the obstacles he must overcome to use black players in the Philadelphia Athletics to get to the World Series.

I haven’t had a chance to review the book yet, but Schilling was gracious enough to provide a guest post about his writing space. And I know how much you love these sneak peeks. Please welcome Peter Schilling.

I work upstairs in my old, 1923 brick house. The upstairs attic was finished sometime probably in the 1980s, and has carpeting, as opposed to the rest of the place, which sports hardwood floors. The attic, or factory as I like to call it, is the perfect writing space. It’s the length of the house, its insulated from noise (so I can work even when someone’s downstairs watching television), has its own bathroom, futon, and all the space I need for all my clutter. It is very quiet up here, which I enjoy. You can see down the block from my window and feel the house shake when a train goes by.

As you can see, I write on a white drafting table. I like the slight incline on the surface, and I like the way the surface reflects the light from the outside. Things stand out on that surface–my tchotchke’s, icons, photos, and notes. I have a piece of cloth in the center that I use to write on, which my father made and on which he used to perform slight-of-hand magic.

I write my first drafts in longhand, using a Mont Blanc fountain pen a friend gave me, in black journals. Then I pull out my MacBook and transcribe. Surrounding my desk, and in arm’s reach (it’s hard to get in and out), I have a dictionary, thesaurus, the Complete Film Dictionary (I’m writing a screenplay), other books for research, pen cartridges, journals, note cards, and, on the walls, various items that interest or inspire: a current tide calendar from where my wife and I honeymooned, photos of people I admire (Jackie Robinson, Bill Veeck, Alfred E. Neuman, Robert Mitchum, Mark Fidrych, my father, etc.) And a big poster of “Mulholland Dr.“, because I’m in awe of that movie.

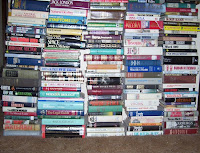

The rest of the space is filled with eight bookshelves, filled with baseball books, novels and pulpy paperbacks, poetry, film biographies, comic books, you name it. There’s old train maps from the Milwaukee Line, vintage baseball pennants (Tigers, Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Athletics), movie posters (Marty, Sullivan’s Travels, The Third Man), and even graffiti I wrote to try and remember the vocabulary of the Navy for my first novel (for instance, in giant scrawl is written “This is a HATCH” by a door).

Now and again I head out to the University of Minnesota’s Wilson Library to get out of the place (which at times feels like I’m in my own head), or to Bob’s 33 Cafe just for a change of pace.This is the space where I spend most of my life, a good six to eight hours a day from about seven in the morning to around three in the afternoon. Everything in here connects to the people and places I’m writing about–the books have inspired certain characters, or I’ve grabbed one or two and tried to figure out how another author managed to structure plot, etc. Surrounding myself with the work of these artists is fun, exciting, and very inspirational. It makes me feel like a part of this world, and it informs all my writing.

Thanks, Peter, for showing us your writing space. Stay tuned for my review of The End of Baseball.

About the Author:

Peter Schilling has been a sportswriter, film critic, and freelance writer for over seven years, in addition to writing novels, graphic novels, plays and screenplays. Check out his author appearances.

FTC Disclosure: Clicking on title and image links will lead you to my Amazon Affiliate page; No purchase necessary, though appreciated.

© 2010, Serena Agusto-Cox of Savvy Verse & Wit. All Rights Reserved. If you’re reading this on a site other than Savvy Verse & Wit or Serena’s Feed, be aware that this post has been stolen and is used without permission.