Source: Public Library

Paperback, 410 pages

On Amazon, on Kobo

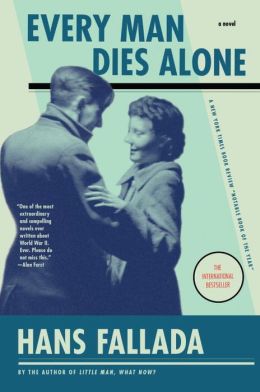

Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier, which was our May book club selection, is a suspenseful story centered around Rebecca de Winter, who by society’s standards was charming, beautiful, and unmatched by other ladies of the upper class. It has been about 10 months to a year since her passing when Maxim de Winter meets a young woman, who remains the unnamed narrator of the story, in Monte Carlo as the paid companion of Mrs. Van Hopper a gossipy and grasping woman who uses any tiny connection to weasel her way into parties, etc. Once her employer contracts influenza, the narrator is free to do what she likes since a private nurses is necessary. As a result, she ends up spending a number of afternoons with the enigmatic Mr. de Winter and later agrees to marry him.

“The woods, always a menace even in the past, had triumphed in the end. They crowded, dark and uncontrolled, to the borders of the drive. The beeches with white, naked limbs leant close to one another, their branches intermingled in a strange embrace, making a vault above my head like the archway of a church.” (page 1)

While my copy’s jacket cover speaks of the novel as a “classic tale of romantic suspense,” there was little romance between the unnamed narrator and Mr. de Winter. While the new Mrs. de Winter is naive and unable to cope with running a magnificent household like Manderlay, she has zero backbone, even as Mrs. Danvers, the home’s housekeeper, plays the dirtiest trick on her. This narrator is an unlikeable character from the start with her whiny nature and her inability to speak her mind, even to her husband. Even though in this time period, women were supposed to be obedient and meek, they also were expected to run entire households with a forceful hand. The new Mrs. de Winter is Rebecca’s antithesis in every way.

“I listened to them both, leaning against Maxim’s arm, rubbing my chin on his sleeve. He stroked my hand absently, not thinking, talking to Beatrice.

‘That’s what I do to Jasper,’ I thought. ‘I’m being like Jasper now, leaning against him. He pats me now and again, when he remembers, and I’m pleased, I get closer to him for a moment. He likes me in the way I like Jasper.'” (page 103)

Neither of the main characters are likeable, as the retrospective narrative keeps readers at a distance from their love affair and their romance. The highlights of the novel were the comical Mr. Favell, Rebecca’s first cousin, and Beatrice, who is plain spoken. Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier is suspenseful, though ridiculous at times, and there are highly descriptive paragraphs about nature. The narrative is bogged down by the descriptions and the dream-like conversations she has with herself about upcoming events and confrontations. While the plot is interesting, it is tough to feel empathy for the main narrator and to cheer her on.

Daphne was born in 1907, grand-daughter of the brilliant artist and writer George du Maurier, daughter of Gerald, the most famous Actor Manager of his day, she came from a creative and successful family.

The du Maurier family were touring Cornwall with the intention of buying a house for future holidays, when they came across “Swiss Cottage”, located adjacent to the ferry at Bodinnick. Falling in love with the cottage and its riverside location, they moved in on May 14th, 1927, Daphne had just turned 20.

She began writing short stories the following year, and in 1931 her first novel, ‘The Loving Spirit’ was published. It received rave reviews and further books followed. Then came her most famous three novels, ‘Jamaica Inn’, ‘Frenchman’s Creek’ and Rebecca’. Each novel being inspired by her love of Cornwall, where she lived and wrote.

What the Book Club Thought:

The book club had a mixed reaction to this one; there were several members who enjoyed the story, but not the descriptions of nature. There were too many words, one member said. Others saw the background of the narrator as an obstacle she needed to overcome in order to mature. One member pointed out that the narrator — even in retrospect — did not seem to offer any judgment about herself and behaviors, leaving readers to wonder whether she had matured at all. The whiny nature of the character was tough to take for some readers, while other were interested in her little internal debates about others’ reactions to her actions or the actions she could have taken. A few did not see the relationship between Max and the new wife as very loving, especially when she talks about him petting her like a dog.

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author: